INTRODUCTIONRhinoscleroma is a chronic granulomatous infectious disease that compromises the respiratory tract mucosa (most frequently in the nose) and may eventually extend to the lower airways (the larynx, trachea, and bronchi). Recently, practitioners have adopted the term scleroma (1,2). It was first described by Ferdinando Von Hebra in 1870 (3).

LITERATURE REVIEWRhinoscleroma is an infectious disease caused by the bacterium Klebsiella rhinoscleromati, an encapsulated gram-negative member of Enterobacteriaceae that can be isolated by culture medium. It is considered endemic to some countries of Africa, Central America, and South America, but is rare in Brazil (4). It is associated with some predisposing factors such as low socioeconomic status, poor hygiene, immunodepression, and contact with infected patients (5).

The disease develops insidiously from the nasal mucosa, and progression occurs in 3 phases: catarrhal (characterized by rhinorrhea, crusting, and nasal obstruction, often confused with simple rhinitis); granulomatous (where nodes are found in the submucosa and infiltrating lesions); and sclerotic (marked by gross scar tissue, which may occur in the vestibule and/or in larynx stenosis) (1). The differential diagnoses include neoplasms and other inflammatory conditions such as leprosy, paracoccidioidomycosis, sarcoidosis, and Wegener granulomatosis (6).

Diagnosis can be confirmed by culture (with 50% to 60% positive specificity) or by histopathology. Treatment consists of antibiotic therapy and, in some cases, surgery

(1, 2, 7).

CASE REPORTA 28-year-old housewife presented to the Otorhinolaryngology Service of Brasilia's University Hospital complained of obstruction in both nostrils since the past 3 years, significant loss of sleep, and frequent headaches in the frontal region. She denied vocal alterations or dyspnea. She reported that 2 years ago she underwent unsuccessful nasal surgery for synechia resection. At that time, no biopsy was performed.

She denied drug use, nasal trauma, immunological deficiency, or family history of similar symptoms. She has never been a smoker or an alcoholic.

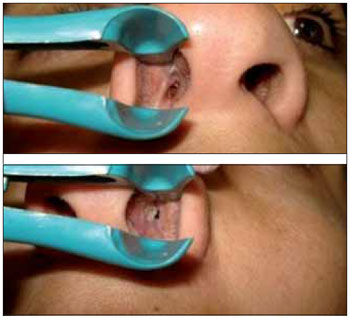

On examination, she presented with significant nasal pyramid bulging. Previous rhinoscopy showed a lesion with a granulomatosis aspect, occupying both nasal cavities near the vestibule (Picture 1). Laryngoscopy was normal.

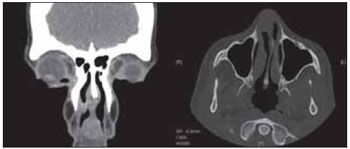

Computed tomography of the paranasal sinuses showed soft tissue material occupying the lower portion of the nasal cavities without maxillary sinus involvement. There were no signs of bone destruction (Picture 2).

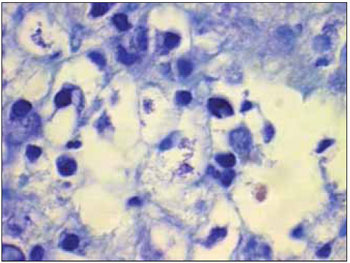

The patient underwent biopsy of the lesion under local anesthesia, and pathology revealed diffuse infiltration of distended and vacuolated histiocytes with rounded nuclei located eccentrically (Mikulicz cells) (Picture 3). Giemsa, PAS, and Warthin-Starry staining revealed intracytoplasmic bacilli. These findings established the diagnosis of rhinoscleroma.

The treatment was tetracycline therapy (500 mg every 6 hours per 30 days).

There was partial reduction in the lesion size. We added concomitant gemifloxacin (320 mg/day for 2 weeks). After completing this antibiotic cycle, there was complete lesion remission, although slight cicatricial stenosis of the nasal cavities remained. Given the significant clinical improvement, the patient chose not to undergo further surgical treatment.

Picture 1.

Picture 2.

Picture 3.

The patient presented with the classical symptoms of rhinoscleroma, restricted to the nasal mucosa. Nevertheless, the disease can affect other respiratory tract regions, such as the larynx (15-40%), nasopharynx (18-43%), paranasal sinuses (26%), trachea (12%), and bronchi (2-7%) (5).

Histopathological analysis validated the diagnosis by revealing the presence of classical Mikulicz cells (histiocytes containing bacillus) or Russell corpuscles (plasma cells with hyaline degeneration). These findings are easily recognized when the disease is in the granulomatous stage. The diagnosis can also be defined by culture medium, which has 50% to 60% specificity (3).

Several antibiotics can be used to treat rhinoscleroma. Tetracycline or streptomycin is typically used for a minimum period of 4 weeks. Quinolones have also been proven effective, with the advantage of fewer side effects (2). We chose gemifloxacin in our case because it is the only respiratory quinolone available freely to the patients in this ambulatory clinic.

FINAL COMMENTSIn addition to its rarity in Brazil, the diagnosis of rhinoscleroma can be especially difficult due to several factors such as differential diagnosis, limited sensitivity of diagnostic methods, and varying form of presentation depending on the disease stage.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES1. Canalis FR, Zamboni L. An Interpretation of the Structural Changes Responsible for the Chronicity of Rhinoscleroma. Laryngoscope. 2001, 111:1020-6.

2. Simons ME, Granato L, Oliveira RC, Alcantara MP. Rinoscleroma: relato de caso. Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol. 2006, 72(4):568-71.

3. Von Frisch A. The etiology of rhinoscleroma. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1882, 32:969-2.

4. Hart CA, Rao SK. Editorial: Rhinoscleroma. J Med Microbiol. 2000, 49:395-6.

5. Chan TV, Spiegel JH. Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis of the membranous nasal septum. J Laryngol Otol. 2007, 121:998-1002.

6. Andraca R, Edson R, Kern E. Rhinoscleroma: a growing concern in the United States? Mayo Clinic experience. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993, 68:1151-7.

7. Badia L, Lund VJ. A case of rhinoscleroma treat with ciprofloxacin. J Laryngol Otol. 2001, 115:220-2.

1) Resident Physician in Otolaryngology at University Hospital of Brasilia

2) Resident Physician in Pathology at University Hospital of Brasilia

3) Doctor in Otolaryngology. Otolaryngologist at University Hospital of Brasilia

4) Doctorate in Medicine by University of Minnesota. Professor at University of Brasilia and Head of Otorhinolaryngology Department of University Hospital of Brasilia

Institution: University Hospital of Brasilia. Brasilia/DF - Brazil. Mailling address: Igor Teixeira Raymundo - SHIN QI 10 conj. 10 CS 08 Lago Norte - Brasília / DF - Brazil - Zip Code: 71525-100.

Article received on September 3, 2009. Article accepted on October 3, 2009.